Dissecting Recent Conclusions on the Attention-Emotion Link at ARF

The recent ARF AUDIENCExSCIENCE conference provided a platform for the latest research on attention in advertising. The strength of the experimental designs and the eagerness to advance industry knowledge were clearly on display. We came away with important new knowledge. We came away with immediate, impactful applications. Yet, we also came away with important questions for us to consider as an industry.

The following review of Nielsen’s presentation on attention provides an example of important new knowledge that also raises important questions for our industry. Through their analysis of over 500 advertisements, they’ve challenged some fundamental assumptions about how we measure and interpret attention in advertising. While their contribution advances important conversations about attention measurement, their conclusions warrant scrutiny from both methodological and theoretical perspectives.

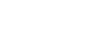

The presenters make an important point that attention is more than just “eyes on screen.” As illustrated in the image to the left, the number of eyes on the screen can be the same while the quality of the attention can differ greatly (e.g., focused vs. scattered attention). They also provided valuable insights into different patterns of neurological processing, identifying distinct scenarios where high attention doesn’t necessarily translate to better advertising outcomes.

However, conclusions require careful examination of the methodology and measures.

The Measurement vs. Construct Problem

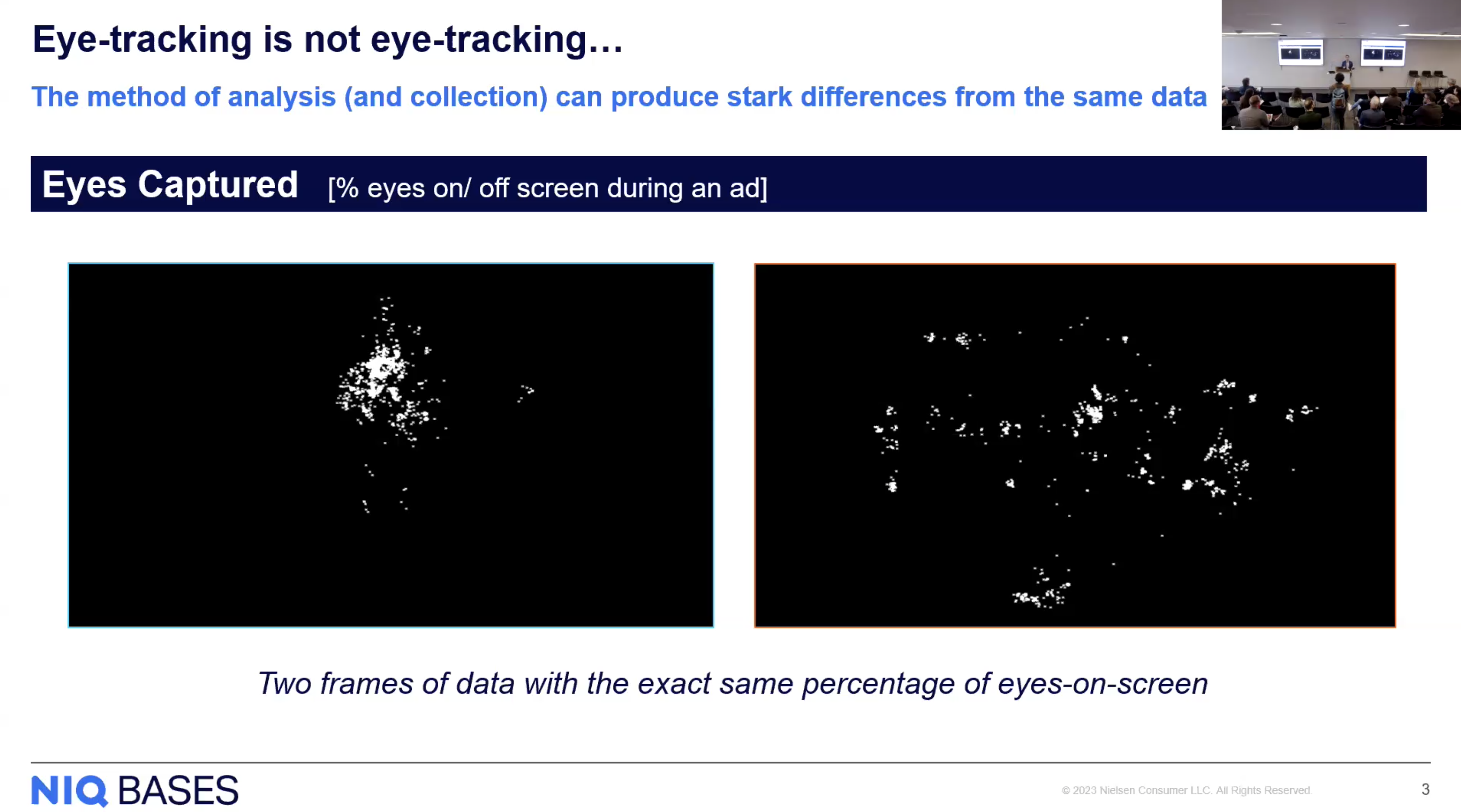

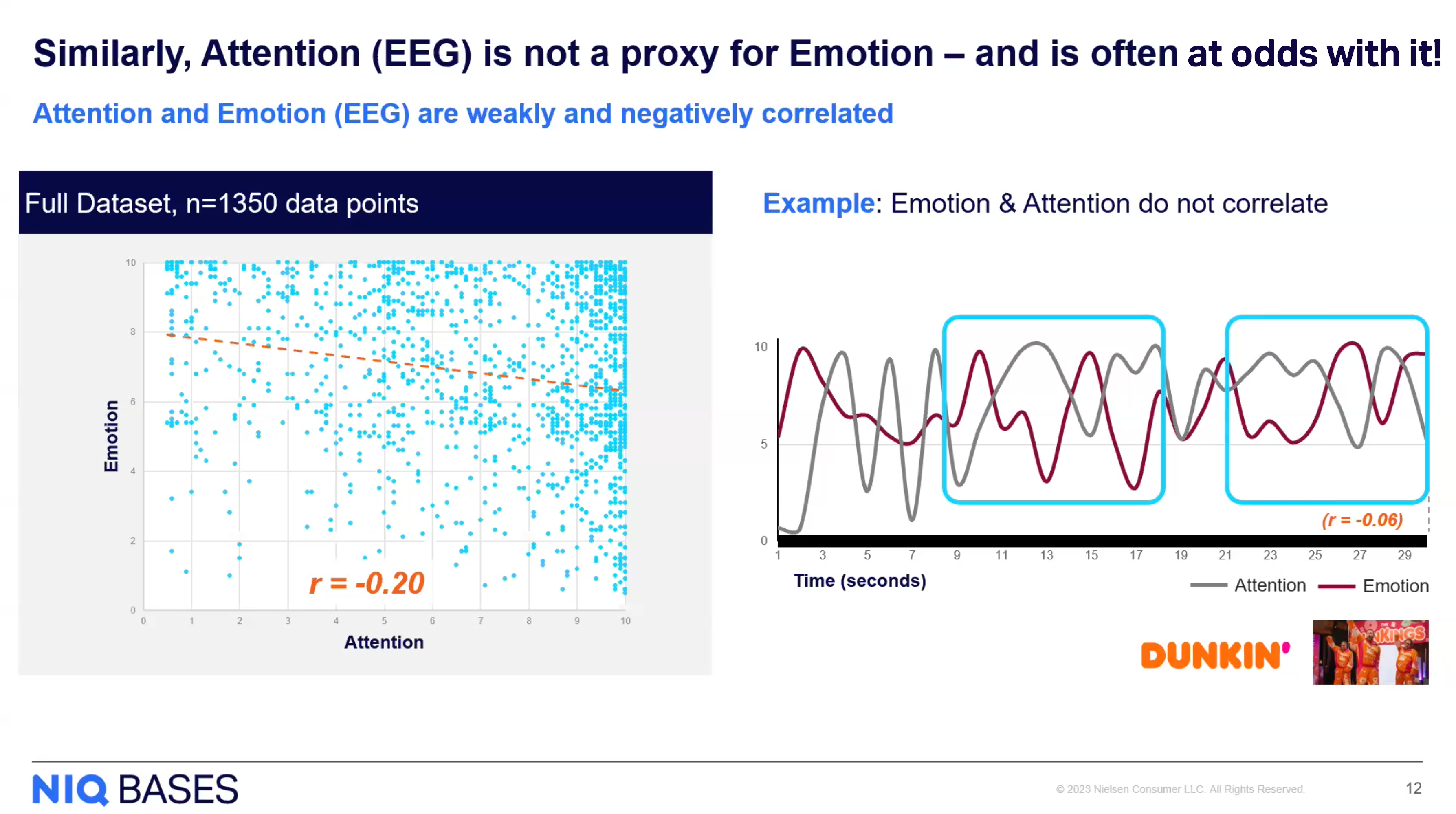

The core issue lies in how Nielsen moves from measurement relationships to construct conclusions. For example, when they report no correlation between attention and emotion (r = -0.20), they’re actually reporting no correlation between their specific measures of attention and emotion. This distinction isn’t merely academic—it’s fundamental to how we interpret and apply these findings.

Consider the temporal dynamics of emotional response. When we watch an advertisement, there’s naturally a delay between attending to content and experiencing an emotional response. Without additional detail from the presenters, it appears that the analysis of attention and emotion uses concurrent timestamps for both measures—essentially looking for relationships between attention and emotion at the same moments in time. This approach virtually guarantees weak correlations, not because attention and emotion are unrelated, but because the analysis framework fails to capture their natural temporal relationship.

The Reliability Question

We also need to consider measurement reliability. The EEG measures employed in this study, particularly for emotional response, typically show considerable noise even in controlled laboratory conditions. Frontal asymmetries in alpha wave activity, while theoretically sound markers of approach/avoidance tendencies, often demonstrate small effect sizes and substantial within-subject variability.

This brings us to a critical point: when we observe no correlation between measures, is it because the underlying constructs are unrelated, or because our measurements contain too much noise to detect the relationship?

The Range Restriction Problem

Looking at Nielsen’s data visualizations reveals another methodological concern: clear ceiling effects in both attention and emotion measures. When measurement scales artificially constrain the range of possible responses, we limit our ability to detect true relationships between variables. This is particularly evident in their scatterplots where data points cluster in the upper ranges of both metrics.

Moving Beyond Simple Correlations

What’s particularly interesting about Nielsen’s approach is their implicit assumption that relationships between attention and emotion should be linear. But what if the relationship is more complex? What if attention serves as a gateway for emotional processing, but the strength of emotional response depends on content relevance and individual differences?

These questions highlight why we need to be cautious about drawing broad conclusions about psychological constructs based on specific measurement approaches.

A Path Forward

To be clear, the measures are good but the conclusions are reaching. It’s a great reminder that relationships between measures do not equate to relationships between psychological constructs. The work emphasizes several opportunities for the industry to advance our fundamental knowledge of the true drivers of advertising effectiveness:

The Scientific Imperative

As practitioners of applied consumer neuroscience, we have a responsibility to maintain scientific rigor while pushing the boundaries of what’s possible in advertising measurement. This means:

- Acknowledging the limitations of our methods

- Avoiding the temptation to draw overly broad conclusions from specific measurement approaches

- Continuously working to improve our measurement tools and analytical frameworks

While this work advances important conversations about attention measurement in advertising, the conclusions about the relationship between attention and emotion overreach the evidence.

The future of advertising measurement lies not in choosing between attention or emotion metrics, but in developing more sophisticated frameworks that capture how these processes interact to drive advertising effectiveness. Let’s ensure our observations about psychological constructs aren’t merely artifacts of our measurement approaches, but rather reflect meaningful insights about how advertising works.

By: Aaron Reid

Founder & CEO, Sentient Decision Science, Inc.