Ultimatum, coins of emotional fortune, and a brief refutation of game theory

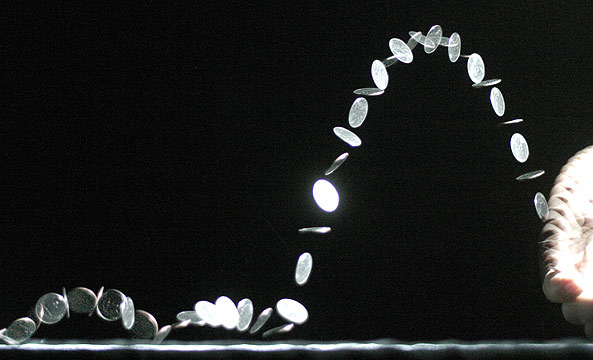

Let’s play a game: There are ten coins on the table. The rules of the game are simple. I propose a way we should split the coins; you can either accept or reject my proposal. If you accept my terms, we get the coins according to my proposed split. If you reject them, we both get nothing. That’s it, and no second chances for positive reciprocity. Sound easy? Well, it’s more complicated than you might think. Let’s play anyway:

How about a 5/5 split? Good deal you say? Of course… that seems fair… who wouldn’t accept that?

What about 6/4, my favor? Perhaps you’re slightly peeved at me, but you’d still be 4 coins richer than you were before we began. I’ll assume that you’d probably accept.

What about 7/3? “Maybe…”

8/2? “I don’t think so…”

9/1? “Of course not… do you think I’m a moron?”

It’s ok to begin rejecting my offers as they become less and less fair; your emotions, in this case, not your rational senses, constitute the threshold by which you can tolerate my greed. We’ll talk about my motivations for doing so later; first we need to map out how the game works, and how it ought to be played if we were purely rational creatures.

Our little game of Ultimatum, is a carefully constructed scenario which demonstrates how premises of Game theory and many other economic models are not descriptive of actual human behavior. According to game theory, individuals are self-maximizing. Any net gain for both individuals, in the coin-game, should be a signal of a well-made decision on both sides. Thus, even if I only offered you 1 coin – keeping 9 for myself – 1 is still greater than 0 and therefore the more rational choice. Game theory is a decision model predicated upon self-interest… “take the coin,” it says, “it’s better than nothing.”

But instead you don’t. Perhaps you even flash me an angry look, mutter an obscenity under your breath, and politely reject my offer. “No thank you. I think we’ll both get bupkis.” And the game is over. In this case, we may both lose economically, but don’t you still feel a slight inkling of victory?

Enough about you; let’s look at me – and by me I really mean the first player (i.e. the player who makes the offer). If operating under a behavioral paradigm predicated upon acting in one’s own self-interest, player A should always make a 9/1 proposition, because this represents the best possible outcome for him. However, if I’m aware that the 9/1 proposition has a higher probability of being rejected than an 8/2 or 7/3 proposition, I may make a different offer.

In this case, I am aware of the potential for emotional interference in my co-player’s rational sense. If I assume you are a completely rational decision-maker, I should always propose a 9/1 split in my favor. But if I assume you to be a completely emotional decision-maker, I have no good rational basis with which to suggest a split. But we do have a sense of how others will respond emotionally, and that, in-turn, affects our own offer. In this case, emotional awareness of the second player would affect our offer to be “more fair.” (An interestingly side note: autistic players are the only ones who consistently split the coins 9:1, as game theory predicts).

Of course, neither game theory nor emotional-exclusivity is a solid explanation of how and why we make our decisions, and that’s why, in behavioral studies, people don’t play the game in the way we’d expect them to.

In fact, the first player almost always suggests a fairly even split, ranging from 50/50 to 60/40 in their favor. Similarly, the second player usually accepts the offer when the coins are fairly split, but will rarely accept and offer that is stacked unevenly in the other player’s advantage from 70/30 to 90/10, despite the ‘logical’ decision to accept any net gain. Perhaps if we return to the psychology behind rejecting the coin offer, we can better understand why the second player would act against his own rational self-interest, letting his emotions trump his economic judgment. Assume now that I’m the second player – capable of rejecting or accepting but not of proposing.

I said that I would reject an offer of 3 coins or less. Why? Well, I could cop-out and say that my decision is purely subjective, a threshold that I arbitrarily selected, but that’s not a very good explanation, nor is it useful. What’s really going on in my head is an emotional judgment, which can be looked at from two different perspectives. On the one hand, the threshold I mentioned before is my tolerance (or lack thereof) to reward or punish your greed. In this case, my motives are altruistic; I reject your 7/3 or 8/2 offer not because I’m stupid, but because I don’t want you to think that it’s ok to exploit people and distribute resources unequally. By accepting a 7/3 (your advantage) offer, I reward your greed; by rejecting a 7/3 offer, I punish your greed, because you get nothing.

The motivation for acting this way clearly stems from a desire for equality, allowing us to hang our hat on a premise something like “people like things to be fair.” I’ll call this altruistic motivation, for now. But altruistic motivation only tells half of the story.

Living at the other end of the emotional spectrum is the same self-interested trait which informed our rational evaluation earlier, but this time it is without any calculated, objective standard. In other words, I may reject your offer, not because I am concerned about fairness, but (to the contrary) because I wish to deny you coins. By accepting an 8/2 offer in your favor, I accept (and help create) a marginalized wealth gap that makes me inferior in any social environment where coins are a valuable resource. By rejecting your offer, I effectively neutralize that threat, but my motivation for rejecting in this case is egoistic, rather than altruistic. Both are non-mutually-exclusive emotional factors creating the same outcome, but for different reasons. Ultimatum doesn’t seem quite as simple anymore, does it?

So what is our top-line conclusion here: that we make emotional decisions? Sure, but we already knew that. Is it that game theory is a poor account of how people make decisions? Yes, but again, Jon Nash had that idea over 40 years ago. Perhaps we can infer something far more subtle: our rational senses are misguided and easily swayed by emotional factors. We’ve always previously assumed that ‘emotional factors’ were highly irregular, inaccessible, subjective, and often as motley and varicolored as any international population sample. And yet here it seems that two different players, will make statistically similar emotional decisions, depending on their role in the game.

I’m arguing that ‘emotional factors’ don’t just come from our relationships with other people; Ultimatum played between two (non-autistic) strangers illustrates similar results, no matter the players. Ah, now we’re onto something larger: emotions, though irrational, are not unpredictable. For in the case of our little resource allocation game, we can explain irrational behavior through two different lenses of altruistic and egoistic emotions which produce the motivation to act in irrational ways.

How many other irrational decision paradoxes can be explained through the lenses of emotion & motivation (see Reid & Gonzalez-Vallejo for emotional explanation of the certainty effect and framing effects)? And how can we begin to catalog these effects into a unifying theory? The beginning of an efficient scale can be found in Aaron Reid’s proportion of emotion model. Could PoE account for the emotional effects found in the Ultimatum game? Give me a month to run the study through the Sentient Consumer Subconscious Research Lab, and I’ll get back to you.

Further Reading:

- The Ultimatum Conundrum – Alan H. Karp, Kay-yut Chen, Ren Wu

- Ultimatum Game with Responder Competition: a Neuroeconomic Study – MarjaLiisa Halko, Yevhen Hlushchuk, Martin Schürmann

- Ultimatum Bargaining Experiments: The State of the Art – J.Neil Bearden

Trackbacks/Pingbacks